CANADA HISTORY - War

War of 1812

The Principles of War can be illustrated by small campaigns as well as great, and by old campaigns as well as those of our own times. It would be difficult to find a series of operations providing a much better object lesson than those of 1812 in which Major-General Sir Isaac Brock defeated the attempt of superior United States forces to conquer the Province of Upper Canada. This campaign, fought nearly a century and a half ago against an adversary who is now the fast friend and essential ally or Canada, will repay study by anyone seeking enlightenment as to the qualities that make a great commander.

The Situation at the Outbreak of fighting

When the United States declared war in June 1812, General Brock was in command of the forces in Upper Canada and was also temporarily administering the civil government of the province. The military problem that faced him was one of extreme difficulty, for the force at his disposal was very small and the boundary line to be defended was very long.

There was only one British regiment of the line in Upper Canada. This was the 41st (which is now the Welch Regiment). There was also a considerable detachment of the 10th Royal Veteran Battalion, another of the Royal Newfoundland Fencibles (chiefly used as marines on the Lakes) and one artillery company. Behind these regular forces stood the provincial Militia, which was simply the men of military age organized in paper battalions on a basis of universal service, and at the outbreak of war virtually without training. A considerably larger British force, including five battalions of the line, was stationed in Lower Canada. All told, the two Canada’s (now Ontario and Quebec) were defended by roughly 7000 troops fit to be considered regulars; of these, only a little over 1600 were in the upper province.

The United States Government had of course a relatively tremendous reservoir of manpower to draw upon, but its regular army was small. Though the establishment when war broke out was more than 35,000 all ranks, the actual strength was much less. The total number of regulars serving may have been in the vicinity of 13,000. Moreover, a large proportion of these were very recent recruits, and the effective force was certainly not superior to the British regulars in the Canadas alone. During the war, the United States called into service over 450,000 militiamen; but the average efficiency of these citizen soldiers, as events on the battlefield amply showed, was decidedly low.

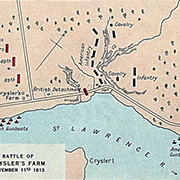

The greater part of the British force had, however, to be retained in Lower Canada, for strategically this was the most important part of the country. Had the Americans followed a sound line of operations, they would have concentrated against Montreal, using the excellent communications available by Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River. The capture of Montreal would have severed the essential line of communication that by the St. Lawrence-on which the defence of Upper Canada entirely depended, and the whole of that province would have fallen into their hands at an early date. The Americans, however, instead of acting in this manner, operated mainly against the frontier of Upper Canada, chopping at the upper branches of the tree rather than the trunk or the roots. In a long view this was fortunate, but it meant that the first shock of their attack had to be met by very inadequate British forces.

In the first months of the war, however, the defenders had one decided advantage: they possessed a distinct naval superiority on the Great Lakes. This was due to the existence of the force known as the Provincial Marine of Upper Canada. In a naval sense this force was very inefficient (it was primarily a transport service and was administered by the Quartermaster-General's Department of the Army); but its armed vessels were superior to anything possessed by the Americans on the Lakes in the beginning, and it was in great part responsible for the preservation of Upper Canada in the first campaign. It must be noted that at this time the land communications of the province were extremely primitive, the roads being very few and very bad. Only by water could troops be moved with any speed.

Against this advantage we must balance a disadvantage. A large proportion of the population of Upper Canada were recent immigrants from the United States, people who could not be expected to come forward to repel an American invasion. Many other Upper Canadians, though loyal enough in a passive way, considered that the Americans' superiority in physical strength made defence useless. In view of the Canadian schoolbook legend of 1812, it may come as a surprise to some people to know that in July Brock wrote to the Adjutant General at Headquarters in Lower Canada as follows:

My situation is most critical, not from any, thing the enemy can do, but from the disposition of the people - The population, believe me is essentially bad - A full belief possesses them all that this Province must inevitably succumb - This prepossession is fatal to every exertion - Legislators, Magistrates, Militia Officers, all, have imbibed the idea, and are so sluggish and indifferent in all their respective offices that the artful and active scoundrel is allowed to parade the Country without interruption, and commit all imaginable mischief . .

What a change an additional regiment would make in this part of the Province! Most of the people have lost all confidence I however speak loud and look big.

No commentary upon the campaign of 1812 should overlook this element in the situation. With greatly superior forces assembling on the frontier, and with the morale of the population (which was largely identical with the Militia) at such a low ebb, many a commander would have adopted a supine defensive attitude. It was the greatness of Brock that, far from allowing these circumstances to discourage him, he realized that the best hope of carrying out his task successfully lay in assuming a vigorous local offensive.