CANADA HISTORY

Samuel De Champlain

Samuel de Champlain, often hailed as the "Father of New France," stands as one of the most influential figures in Canadian history. His efforts in establishing Quebec City and extending French influence throughout the St. Lawrence River Valley and the Great Lakes Basin laid the foundation for what would become modern Canada. Champlain's life, his explorations, and his interactions with Indigenous peoples significantly shaped the early colonial landscape, ensuring that France would play a central role in the development of North America. His legacy is deeply intertwined with the early history of New France, exploration, and the fur trade.

Champlain was born in 1580 in the seaport town of Brouage, on the west coast of France, at a time when France was engaged in wars of religion between Catholics and Protestants. Unusually for his time, Champlain was a Protestant, and this background would have given him a unique perspective within Catholic-dominated France. From an early age, Champlain was immersed in the maritime world, where he learned the vital skills of navigation, cartography, and seamanship—skills that would prove invaluable in his later life as an explorer.

By 1603, Champlain had become involved with a group of French entrepreneurs interested in expanding the lucrative fur trade. That year, he embarked on his first voyage to North America aboard the Bonne-Renommee, charting the St. Lawrence River and producing detailed maps of the region. His work, "Des Sauvages: ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouages, faite en la France nouvelle l'an 1603," which he published upon his return, offered one of the earliest detailed accounts of the geography and peoples of the area. This journey was pivotal for Champlain, igniting his lifelong dedication to New France and establishing him as a key figure in French exploration.

Recognizing his talents, King Henry IV of France commissioned Champlain to explore further and report on the potential of France’s colonial interests in the Americas. In 1604, Champlain joined an expedition to establish a settlement on Saint Croix Island, in the Bay of Fundy. However, after a harsh winter that decimated the colony, the settlers relocated to Port Royal in present-day Nova Scotia. Port Royal would serve as an important base for further explorations along the Atlantic coast. Between 1605 and 1606, Champlain mapped the coastlines of Maine, Massachusetts, and beyond, but he found no suitable locations for new settlements.

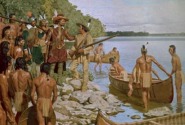

In 1608, Champlain launched what would become his most significant expedition. Sailing from Honfleur, France, he arrived at Tadoussac, on the St. Lawrence River, before journeying further upstream to the abandoned Iroquois village of Stadacona, the site where Jacques Cartier had once landed during his expeditions in the 1530s. On July 3, 1608, Champlain and his settlers landed and established Quebec City, making it the first permanent European settlement in Canada. This moment marked the true beginning of French colonization in North America.

The settlement faced immediate challenges. The first winter was brutal, with harsh weather, disease, and scurvy taking the lives of twenty of the twenty-eight settlers. Nonetheless, Champlain's vision for New France remained steadfast. By 1609, he had established relations with several Indigenous groups, including the Huron, Algonquin, Montagnais, and Etchemin peoples. These alliances were crucial for the survival and expansion of the French presence in the region, particularly as they opened up the fur trade, which became the economic backbone of New France.

Champlain’s relationships with the Indigenous peoples were complex, shaped by mutual interests but also by conflict. In 1609, Champlain agreed to support his Algonquin and Huron allies in their ongoing war with the powerful Iroquois Confederacy. This decision would set the stage for over a century of conflict between the French and the Iroquois, with profound implications for the future of the colony. Champlain’s first major engagement with the Iroquois took place on July 30, 1609, near present-day Crown Point, New York, on the shores of Lake Champlain. Armed with his arquebus, a primitive firearm, Champlain killed two Iroquois chiefs, a shocking display of European firepower that scattered the Iroquois warriors and secured a temporary victory for his Algonquin allies. This battle was the first recorded instance of the Iroquois encountering European weaponry, and it solidified a French alliance with t

he Huron and Algonquin, while driving a wedge of enmity between the French and the Iroquois Confederacy—a dynamic that would persist for the next 150 years.

Champlain’s return to France in the fall of 1609 allowed him to seek additional support for his efforts in New France. Upon his return to the colony in 1611, Champlain traveled upriver from Quebec to the site of Hochelaga, where Jacques Cartier had once landed. Here, Champlain laid the groundwork for what would eventually become Montreal, further expanding French influence in the region. His continued efforts to strengthen alliances with Indigenous peoples, explore the interior, and open new trade routes were all part of a larger French strategy to expand their territorial claims and establish a permanent French presence in North America.

Champlain’s personal life also intertwined with his colonial ambitions. In 1610, he married Hélène Boullé, a young girl of 12 years, as part of an arrangement that provided Champlain with a dowry to support his colonizing efforts. Though unusual by modern standards, this marriage reflected the social and political arrangements of the time, where marriages were often used to secure alliances and financial backing.

Champlain’s relationships with the Indigenous peoples were complex, shaped by mutual interests but also by conflict. In 1609, Champlain agreed to support his Algonquin and Huron allies in their ongoing war with the powerful Iroquois Confederacy. This decision would set the stage for over a century of conflict between the French and the Iroquois, with profound implications for the future of the colony. Champlain’s first major engagement with the Iroquois took place on July 30, 1609, near present-day Crown Point, New York, on the shores of Lake Champlain. Armed with his arquebus, a primitive firearm, Champlain killed two Iroquois chiefs, a shocking display of European firepower that scattered the Iroquois warriors and secured a temporary victory for his Algonquin allies. This battle was the first recorded instance of the Iroquois encountering European weaponry, and it solidified a French alliance with t

Champlain’s relationships with the Indigenous peoples were complex, shaped by mutual interests but also by conflict. In 1609, Champlain agreed to support his Algonquin and Huron allies in their ongoing war with the powerful Iroquois Confederacy. This decision would set the stage for over a century of conflict between the French and the Iroquois, with profound implications for the future of the colony. Champlain’s first major engagement with the Iroquois took place on July 30, 1609, near present-day Crown Point, New York, on the shores of Lake Champlain. Armed with his arquebus, a primitive firearm, Champlain killed two Iroquois chiefs, a shocking display of European firepower that scattered the Iroquois warriors and secured a temporary victory for his Algonquin allies. This battle was the first recorded instance of the Iroquois encountering European weaponry, and it solidified a French alliance with t

he Huron and Algonquin, while driving a wedge of enmity between the French and the Iroquois Confederacy—a dynamic that would persist for the next 150 years.

Champlain’s return to France in the fall of 1609 allowed him to seek additional support for his efforts in New France. Upon his return to the colony in 1611, Champlain traveled upriver from Quebec to the site of Hochelaga, where Jacques Cartier had once landed. Here, Champlain laid the groundwork for what would eventually become Montreal, further expanding French influence in the region. His continued efforts to strengthen alliances with Indigenous peoples, explore the interior, and open new trade routes were all part of a larger French strategy to expand their territorial claims and establish a permanent French presence in North America.

Champlain’s personal life also intertwined with his colonial ambitions. In 1610, he married Hélène Boullé, a young girl of 12 years, as part of an arrangement that provided Champlain with a dowry to support his colonizing efforts. Though unusual by modern standards, this marriage reflected the social and political arrangements of the time, where marriages were often used to secure alliances and financial backing.

In 1609 In 1613, Champlain embarked on another significant expedition, this time exploring the Ottawa River and into the Great Lakes region, traveling as far as Lake Nipissing and Georgian Bay. His extensive travels through the network of rivers and lakes in present-day Ontario and Quebec highlighted the vital importance of the Indigenous birchbark canoe, which allowed for efficient travel across vast distances. Champlain's expeditions into the interior opened up new trade routes and strengthened France's foothold in the fur trade, which was increasingly becoming the colony’s primary economic engine.

In 1609 In 1613, Champlain embarked on another significant expedition, this time exploring the Ottawa River and into the Great Lakes region, traveling as far as Lake Nipissing and Georgian Bay. His extensive travels through the network of rivers and lakes in present-day Ontario and Quebec highlighted the vital importance of the Indigenous birchbark canoe, which allowed for efficient travel across vast distances. Champlain's expeditions into the interior opened up new trade routes and strengthened France's foothold in the fur trade, which was increasingly becoming the colony’s primary economic engine.

Champlain’s exploration of the Great Lakes culminated in his involvement in a failed military expedition in 1615. Leading a group of Huron warriors, Champlain traveled to what is now central New York, where they attempted to attack an Iroquois village. The attack was unsuccessful, and Champlain was wounded in the leg by two arrows, forcing him to retreat to the Huron homeland for the winter. Despite the failure of the campaign, Champlain used this time to learn more about Huron culture, solidifying his ties with his Indigenous allies and gaining valuable knowledge about the region.

Throughout his career, Champlain balanced his duties as an explorer, a diplomat, and a colonial administrator. By 1620, he had been appointed Lieutenant Governor of New France, and he spent the next 15 years managing the colony, expanding trade, and exploring new territories. Champlain’s governance of New France laid the foundations for the colony's development, overseeing the establishment of settlements, the fur trade, and relations with Indigenous groups.

Champlain passed away in 1635, but his legacy as the founder of Quebec City and the architect of New France endured. His vision of a French colonial empire in North America had been realized, and his efforts paved the way for the continued expansion of French influence throughout the continent. Quebec City, which he founded in 1608, remains one of the oldest cities in North America, a testament to Champlain's enduring impact on Canadian history.

Champlain passed away in 1635, but his legacy as the founder of Quebec City and the architect of New France endured. His vision of a French colonial empire in North America had been realized, and his efforts paved the way for the continued expansion of French influence throughout the continent. Quebec City, which he founded in 1608, remains one of the oldest cities in North America, a testament to Champlain's enduring impact on Canadian history.

The importance of Samuel de Champlain’s work cannot be overstated in the context of Canadian history. His explorations opened up vast territories for French influence, his diplomatic efforts with Indigenous peoples shaped the political landscape of the region, and his establishment of Quebec City ensured that France would have a lasting presence in North America. Champlain's role in the fur trade, his exploration of the Great Lakes, and his leadership in New France solidified him as one of the most significant figures in the early history of Canada. Through his vision, determination, and resilience, Champlain helped shape the course of Canadian history, earning him the title "Father of New France."

Champlain oversaw the coming of the Jesuit Order in New France and their efforts at converting the natives to Christianity.

He administered and continued to explore eastern Canada for the next 20 years and on December 25, 1635 he died after suffering a stroke a month previously.

THE VOYAGES TO THE GREAT

RIVER ST. LAWRENCE BY THE

SIEUR DE CHAMPLAIN, . . .

FROM THE YEAR 1608 UNTIL

1612

Credit for establishing the first permanent settlement in

Canada belongs to Samuel de Champlain, "The Father of

New France." Born in France in 1567, Champlain made

his first voyage to the St. Lawrence region in 1603, and

in 1604 he took part with De Monts in an abortive at

tempt to establish a French colony in Acadia. It was on

his third voyage, in 1608, that he succeeded in founding

a settlement at Quebec. From his base at Quebec he made

further explorations, discovering Lake Champlain and

exploring the Ottawa Valley. In 1615 he reached Georgian Bay by way of the Ottawa River and Lake Nipissing.

The documents given here describe Champlain's arrival at

Quebec, the construction of the first buildings in the settlement, and the difficulties of the first winter.

. . . From the island of Orleans to Quebec is one

league, and I arrived there on July the third [ 1608 ]. On

arrival I looked for a place suitable for our settlement, but

I could not find any more suitable or better situated than

the point of Quebec, so called by the natives, which was

covered with nut-trees. I at once employed a part of our

workmen in cutting them down to make a site for our

settlement, another part in sawing planks, another in dig.

H. P. Biggar, ed., The Works of Samuel de Champlain

( Toronto, The Champlain Society, 1925), II, 24-25, 35-

37, 44-45, 52-53, 59, 63.

Cite Article : www.canadahistory.com/sections/documents