CANADA HISTORY

Native Perceptions

The encounters between European explorers and Indigenous peoples in the Americas, including Canada, represent some of the most significant and complex moments in world history. These first interactions shaped the course of colonization, trade, conflict, and diplomacy for centuries to come, with deeply varied outcomes depending on the nature of the explorers' intentions, the specific Indigenous groups they encountered, and the circumstances of their arrival. The diversity in native perceptions of European explorers reflected not only the differences between Indigenous cultures themselves but also the wide range of objectives held by the explorers, from conquest and exploitation to trade and settlement.

In some cases, Indigenous groups greeted the European newcomers with curiosity and even reverence. One of the most famous examples of this is the Aztecs' reception of Hernán Cortés in 1519. The Aztecs, under the rule of Emperor Montezuma II, believed that Cortés and his men might be the fulfillment of a prophecy about the return of the god Quetzalcoatl, who was expected to overthrow the empire. This perception facilitated Cortés' ability to enter the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan and contributed to the empire's eventual downfall. In this instance, Indigenous religious beliefs played a pivotal role in the interaction, though the consequences for the Aztecs were disastrous.

In contrast, other Indigenous groups viewed the European arrivals with suspicion, tolerance, or outright hostility. Some were eager to trade, fascinated by the strange and unfamiliar goods the explorers brought with them—metal tools, cloth, and especially firearms, which were unlike anything the Indigenous peoples had seen before. In the early days of European exploration in Canada, for example, the Mi'kmaq and other groups along the Atlantic coast were initially curious about the Europeans' ships and tools. They saw opportunities for trade, particularly in acquiring iron goods and weapons that could enhance their own status and power within existing Indigenous trade networks.

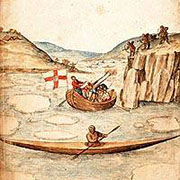

Yet, for many Indigenous communities, the Europeans were seen as strange visitors who were to be tolerated for a time but ultimately expected to leave. The French explorer Jacques Cartier, for instance, was greeted with cautious curiosity when he arrived in the St. Lawrence Valley in 1534. The St. Lawrence Iroquoians of Stadacona (near present-day Quebec City) and Hochelaga (near present-day Montreal) were open to limited interaction with Cartier, but their patience quickly wore thin as they realized that the French had no intention of departing. Cartier's efforts to establish a foothold in the region were met with increasing resistance, especially when his men kidnapped Chief Donnacona and several other Iroquoians to present them to the French court. This betrayal eroded whatever goodwill had existed between the French and the St. Lawrence Iroquoians.

In some instances, Indigenous groups saw the European arrivals as potential allies, particularly in regions where intertribal conflicts existed. In the early 1600s, when Samuel de Champlain founded Quebec, the French aligned themselves with the Algonquin, Huron-Wendat, and Montagnais peoples, who were locked in conflict with the Iroquois Confederacy. The French provided firearms and other goods in exchange for furs, thus cementing an alliance that would shape the political landscape of northeastern North America for decades. However, this relationship also meant that the French would be drawn into the complex web of Indigenous rivalries and conflicts, resulting in ongoing warfare with the Iroquois.

While these interactions could lead to cooperation and trade, they were also fraught with tension, misunderstanding, and exploitation. Nowhere was this more evident than in the encounters with Spanish conquistadors. The Spanish, driven by a desire for wealth and power, often viewed the Indigenous peoples they encountered as inferior and ripe for conquest. The brutal subjugation of the Aztec and Inca empires in Central and South America by the Spanish set a precedent for how European colonizers would often treat Indigenous populations—as sources of labor and land to be exploited. The imposition of the encomienda system, which forced Indigenous peoples into labor for the benefit of Spanish settlers, had devastating effects on the native population.

One of the most tragic consequences of these early encounters was the introduction of European diseases to Indigenous populations, who had no immunity to such illnesses. Smallpox, measles, and influenza swept through the Americas in the wake of European contact, decimating Indigenous communities. In many areas, including Canada, the loss of life was catastrophic. Estimates of the number of Indigenous people who died from these diseases range from hundreds of thousands to millions. Entire villages were wiped out, and the social and cultural structures of many Indigenous societies were irreparably damaged. The arrival of European settlers and explorers, while often seen by Europeans as the beginning of a "New World," brought about profound and deadly consequences for Indigenous peoples across the Americas.

In Canada, the Beothuk people of Newfoundland provide a particularly tragic example of the destructive impact of European contact. The Beothuk, who were the first Indigenous group to encounter European fishermen and explorers, were systematically driven from their coastal hunting and fishing grounds by European settlers. European diseases, combined with violent confrontations and the depletion of the Beothuks' resources, led to their extinction by the early 19th century. This pattern of displacement, disease, and conflict was repeated throughout much of Canada as European settlers pushed further into Indigenous territories.

Despite the initial wonder that Indigenous peoples may have felt at the sight of European ships and metal tools, they quickly recognized the limitations and weaknesses of the newcomers. European explorers, who often lacked the knowledge and skills needed to survive in the harsh Canadian wilderness, relied heavily on Indigenous assistance. The early French settlers, for example, were devastated by scurvy during their first winters in Canada, until the Algonquin introduced them to spruce tea, which contained the vitamin C they needed to recover. Similarly, it was Indigenous knowledge of hunting, fishing, and navigation that allowed Europeans to survive in the unfamiliar landscape.

However, the relationship between Indigenous peoples and Europeans was rarely one of mutual benefit. While the initial exchanges of goods and knowledge could be helpful to both parties, the long-term consequences of European colonization were overwhelmingly negative for Indigenous communities. The expansion of European settlements and the imposition of European legal, political, and religious systems gradually eroded Indigenous sovereignty and cultures. Land that had been occupied and managed by Indigenous peoples for millennia was taken over by European settlers, leading to the marginalization and displacement of Indigenous populations.

The clash of cultures, values, and worldviews between Indigenous peoples and European settlers resolved itself in various ways, but more often than not, it resulted in the subjugation and disenfranchisement of Indigenous peoples. Treaties were signed, often under duress or with promises that were later broken. Indigenous lands were seized, traditional ways of life were disrupted, and Indigenous peoples were forced into European-style settlements, missions, or reserves. While there were moments of cooperation, such as the fur trade alliances between the French and various Indigenous groups, these partnerships often masked deeper inequalities and the gradual encroachment of European dominance.

In conclusion, the interactions between Indigenous peoples and European explorers in Canada were complex and varied, shaped by the intentions of the explorers and the responses of the Indigenous groups they encountered. While there were moments of curiosity, trade, and alliance, the long-term consequences of European colonization were devastating for Indigenous communities. The introduction of European diseases, the displacement of Indigenous peoples from their lands, and the imposition of European systems of governance and religion led to profound and lasting changes in the social, cultural, and political landscapes of Canada. These early encounters set the stage for the centuries of colonization that would follow, fundamentally altering the course of Canadian history.

Cite Article : www.canadahistory.com/sections/documents