CANADA HISTORY

Bill of Rights

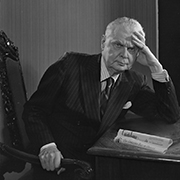

John Diefenbaker, one of Canada’s most influential political leaders, had a long-standing commitment to ensuring the protection of individual rights and freedoms for all Canadians. This dedication to human rights, which had been shaped by his experiences growing up and practicing law, became a defining feature of his political career. His deep concern over the lack of formalized protections for basic civil liberties in Canada drove him to pursue a legislative solution. When he became Prime Minister in 1957, and again after winning a majority government in 1958, Diefenbaker made it a priority to enact legislation that would safeguard fundamental rights. This ambition culminated in the passage of the Canadian Bill of Rights in 1960.

The Historical Context and Diefenbaker’s Vision

Diefenbaker’s desire to codify basic rights for Canadians stemmed from his belief that, despite Canada’s democratic traditions, there was an inherent uncertainty when it came to protecting individual freedoms. Throughout his early life and legal career, Diefenbaker had observed numerous instances where citizens, particularly minorities and Indigenous peoples, faced discrimination and were vulnerable to abuses of power. There was no national framework to protect fundamental rights, and the legal protections that existed were piecemeal and dependent on provincial jurisdictions.

One of Diefenbaker’s core beliefs was that all Canadians should have a legal recourse if their rights were violated, particularly when dealing with the government. He wanted to establish a document that enshrined fundamental rights—such as freedom of speech, equality before the law, and freedom of religion—into law. When Diefenbaker became Prime Minister, he took immediate steps toward realizing his vision of a more just and equal Canada by introducing the Canadian Bill of Rights.

The Passage of the Canadian Bill of Rights in 1960

In 1960, after years of preparation, Diefenbaker successfully introduced the Canadian Bill of Rights, a landmark piece of legislation that aimed to safeguard the rights and freedoms of Canadians. The Bill of Rights outlined several fundamental liberties, including:

The right to life, liberty, and security of the person.

Freedom of religion, speech, assembly, and association.

The right to a fair hearing.

Protection against arbitrary detention and imprisonment.

The right to equality before the law and the protection of the law without discrimination.

The Bill of Rights was the first federal law in Canada to set out a formalized declaration of human rights and freedoms. It was an unprecedented step in Canadian legal history, laying the foundation for the protection of civil liberties. For Diefenbaker, the Bill represented his vision of a just society where all Canadians, regardless of race, religion, or ethnicity, would have equal protection under the law.

However, despite its groundbreaking nature, the Canadian Bill of Rights had significant limitations. One of the most glaring weaknesses was its status as a federal statute, rather than a constitutional amendment. This meant that it applied only to areas of federal jurisdiction, such as criminal law and immigration, and did not have authority over provincial laws. For instance, provinces retained control over civil rights, education, and property laws, meaning that many aspects of daily life—especially those concerning social policy and local governance—remained outside the Bill’s reach.

Furthermore, the Bill of Rights did not have the same binding power as constitutional law. It could be overridden by other legislation, and it was subject to judicial interpretation. One such piece of conflicting legislation was the War Measures Act, which granted the federal government sweeping powers in times of national emergency, even allowing for the suspension of civil liberties. The Bill of Rights, despite its noble intentions, was vulnerable to such overriding laws, limiting its effectiveness as an absolute safeguard of individual freedoms.

The Struggle for Constitutional Amendment

Diefenbaker had originally hoped that the Bill of Rights would become more than just a federal statute. His goal was to have the provinces agree to incorporate the Bill into the Constitution, thereby making it a foundational legal document that would apply uniformly across Canada. However, he was unable to secure the necessary consensus among the provinces for a constitutional amendment. Provincial leaders, particularly in Quebec and Ontario, were concerned about federal overreach and the implications that a national bill of rights might have on provincial autonomy. This resistance from the provinces meant that Diefenbaker’s dream of a comprehensive constitutional bill of rights remained unfulfilled.

Despite these limitations, the Canadian Bill of Rights was a significant milestone. It was the first formal attempt to codify human rights in Canadian law, and it set an important precedent for future efforts to protect civil liberties. The Bill also reflected Diefenbaker’s deep commitment to the idea of equality and justice, values that would continue to influence Canadian legal and political culture.

Legacy and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms

The Canadian Bill of Rights remained an important legal document for over two decades, but its limitations were increasingly apparent. By the 1970s, there was growing momentum for a stronger, more comprehensive approach to human rights in Canada. This movement culminated in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, introduced by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau as part of the Constitution Act, 1982.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms was the culmination of what Diefenbaker had originally envisioned—a constitutional guarantee of rights and freedoms that applied to all Canadians, regardless of whether the issue fell under federal or provincial jurisdiction. The Charter was much more robust than the Bill of Rights, providing protections for a wider range of civil liberties, and it had the full force of constitutional law, meaning that it could not be easily overridden by ordinary legislation.

Despite the Charter’s introduction, the Canadian Bill of Rights did not disappear. It remains in force today and is occasionally invoked in legal cases where it offers protections that may not be covered by the Charter. However, in most respects, the Charter has superseded the Bill of Rights, providing a more comprehensive and enforceable framework for protecting human rights in Canada.

The Lasting Importance of Diefenbaker’s Bill of Rights

Although the Canadian Bill of Rights was eventually eclipsed by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, its significance in Canadian history cannot be understated. It was the first legal document in Canada to formally declare the fundamental rights and freedoms of its citizens, and it set a crucial precedent for the development of human rights law in the country. Diefenbaker’s legacy as a champion of civil liberties endures through his efforts to create a more just society, one in which individual rights are protected against arbitrary government actions.

The Bill of Rights was also a reflection of the broader global movement for human rights that emerged in the aftermath of the Second World War. In this sense, Diefenbaker’s initiative aligned Canada with the growing international recognition of human rights, as embodied in documents like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in 1948.

For Diefenbaker, the passage of the Canadian Bill of Rights was the fulfillment of a personal dream to ensure that all Canadians, regardless of background, would have legal recourse if their rights were violated. It was a significant step toward a more equal and just society, and while it had its flaws, it laid the groundwork for the more expansive rights protections that would come with the Charter.

The Canadian Bill of Rights, passed in 1960 under John Diefenbaker, marked an important moment in Canadian history. Though it had limitations, particularly in its application to only federal jurisdictions and its inability to override conflicting laws, it set a precedent for the protection of human rights in Canada. Diefenbaker’s commitment to civil liberties, equality, and justice continues to shape Canada’s legal landscape, and the Bill of Rights stands as a testament to his vision for a more inclusive and fair society. The Bill’s legacy, though superseded in many ways by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, remains a foundational chapter in Canada’s ongoing commitment to human rights.

Canadian Bill of Rights

An Act for the Recognition and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms [S.C. 1960, c.44]

Preamble

The Parliament of Canada, affirming that the Canadian Nation is founded upon principles that acknowledge the supremacy of God, the dignity and worth of the human person and the position of the family in a society of free men and free institutions;

Affirming also that men and institutions remain free only when freedom is founded upon respect for moral and spiritual values and the rule of law;

And being desirous of enshrining these principles and the human rights and fundamental freedoms derived from them, in a Bill of Rights which shall reflect the respect of Parliament for its constitutional authority and which shall ensure the protection of these rights and freedoms in Canada:

Therefore, Her Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate and House of Commons of Canada, enacts as follows:

PART I

BILL OF RIGHTS

1. It is hereby recognized and declared that in Canada there have existed and shall continue to exist without discrimination by reason of race, national origin, colour, religion or sex, the following human rights and fundamental freedoms, namely,

(a) the right of the individual to life, liberty, security of the person and enjoyment of property and the right not to be deprived thereof except by due process of law;

(b) the right of the individual to equality before the law and the protection of the law;

(c) freedom of religion;

(d) freedom of speech;

(e) freedom of assembly and of association; and

(f) freedom of the press.

2. Every law of Canada shall, unless it is expressly declared by an Act of Parliament of Canada that it shall operate notwithstanding the Canadian Bill of Rights, be so construed and applied as not to abrogate, abridge or infringe or to authorize the abrogation, abridgment or infringement of any of the rights or freedoms herein recognized and declared, and in particular, no law of Canada shall be construed or applied so as to

(a) authorize or effect the arbitrary detention, imprisonment or exile of a person;

(b) impose or authorize the imposition of cruel and unusual treatment or punishment;

(c) deprive a person who has been arrested or detained

(i) of the right to be informed promptly of the reason for his arrest or detention,

(ii) of the right to retain and instruct counsel without delay, or

(iii) of the remedy by way of habeas corpus for the determination of the validity of his detention and for his release if the detention is not lawful;

(d) authorize a court, tribunal, commission, board or other authority to compel a person to give evidence if he is denied counsel, protection against self-crimination or other constitutional safeguards;

(e) deprive a person of the right to a fair hearing in accordance to the principles of fundamental justice for the determination of his rights and obligations;

(f) deprive a person charged with a criminal offence of the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to the law in a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, or of the right to reasonable bail without just cause; and

(g) deprive a person of the right to the assistance to an interpreter in any proceedings in which he is involved or in which he is a party or a witness, before a court, commission, board or other tribunal, if he does not understand or speak the language in which such proceedings are conducted.

3.

(1) Subject to subsection (2), the Minister of Justice shall, in accordance with such regulations as may be prescribed by the Governor General in Council, examine every regulation transmitted to the Clerk of the Privy Council for registration pursuant to the Statutory Instruments Act and every Bill introduced in or presented to the House of Commons by a Minister of the Crown in order to ascertain whether any of the provisions thereof are inconsistent with the purposes and provisions of this Part and he shall report any such inconsistency to the House of Commons at the first convenient opportunity.

(2) A regulation need not be examined in accordance with subsection (1) if prior to being made it was examined as a proposed regulation in accordance with section 3 of the Statutory Instruments Act to ensure that it was not inconsistent with the purposes and provisions of this Part.

4. The provisions of this Part shall be known as the Canadian Bill of Rights.

PART II

5. (1) Nothing in Part I shall be construed as to abrogate or abridge any human right or fundamental freedom not enumerated therein that may have exist in Canada at the commencement of this Act.

(2) The expression "law of Canada" in Part I means an Act of the Parliament of Canada enacted before or after the coming into force of this Act, any order, rule or regulation thereunder, and any law in force in Canada or in any part of Canada at the commencement of this Act that that is subject to be repealed, abolished or altered by the Parliament of Canada.

(3) The provisions of Part I shall be construed as extending only to matters coming within the legislative authority of the Parliament of Canada.

Cite Article : www.canadahistory.com/sections/documents