CANADA HISTORY

Statute of Westminster

The 1926 Imperial Conference in England marked a pivotal moment in the evolution of the British Empire and its relationship with its Dominions, including Canada. At this time, there was a growing demand among the Dominions for greater autonomy over their internal and external affairs, particularly in the wake of World War I. Canada, like other Dominions, had made significant sacrifices during the war, and a strong sense of nationalism had emerged, fueling the desire for more control over its own destiny. The conference culminated in the Balfour Report, a document that recognized these shifts in the British-Dominion relationship and laid the foundation for Canada's march toward full sovereignty.

The Balfour Report was a landmark in the constitutional development of Canada and other Dominions such as Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. It acknowledged that the Dominions were autonomous communities within the British Empire, equal in status to the United Kingdom, and not subordinate to British control in domestic or foreign affairs. One of the most significant aspects of the report was the recognition of the right of each Dominion to advise the Crown concerning its own matters. This meant that Canada, for example, would no longer be bound by decisions made solely in London, and the British government would not have the power to disallow any legislation passed by the Dominion parliaments. This shift marked the beginning of a new era of self-governance for Canada and set the stage for the country’s increasing independence.

The demand for autonomy had been gradually growing in Canada, but it had been intensified by the experiences of the First World War. Canada had contributed immensely to the war effort, with over 600,000 Canadians serving in the military and more than 66,000 losing their lives. The war had created a profound sense of national pride and identity, with Canadians no longer seeing themselves merely as British subjects but as citizens of a distinct and emerging nation. The post-war period saw a growing recognition that Canada needed greater control over its own affairs, including its foreign relations.

The appointment of Vincent Massey as Canada’s first official diplomatic representative to the United States in 1926 was a small but symbolic step in the direction of foreign policy autonomy. Before Massey’s appointment, Canada’s foreign relations were largely managed through the British government. His role as Canada’s Minister to the United States marked the beginning of Canada’s independent diplomatic service and underscored the fact that Canada was starting to speak for itself on the international stage.

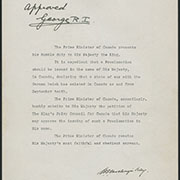

By the time the Statute of Westminster was passed by the British Parliament in 1931, the framework for Canada's independence had already been established by the Balfour Report. The statute gave formal legal recognition to the principles outlined in the Balfour Report and granted the Dominions full legislative independence from Britain, except in areas where they voluntarily chose to remain connected, such as constitutional amendments. For Canada, the Statute of Westminster was a critical turning point. It signaled the end of British legislative control over Canadian affairs, solidifying Canada's status as a sovereign nation within the British Commonwealth.

The British Commonwealth, established by the Statute of Westminster, was defined as "the symbol of the free association of the members of the British Commonwealth of Nations," and marked a new form of political association. Unlike the rigid structure of the Empire, where the colonies and Dominions had been clearly subordinate to Britain, the Commonwealth was based on the principle of equality. This new relationship allowed the Dominions, including Canada, to remain connected to Britain while exercising full control over their own internal and external affairs.

One of the earliest examples of Canada's growing independence occurred during the Chanak Incident in 1922, when Britain requested military assistance from its Dominions to confront a Turkish nationalist uprising in the Middle East. Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, however, refused to commit Canadian forces, marking a significant break from the traditional expectation that Canada would automatically follow Britain’s lead in foreign policy matters. This was followed by another milestone in 1923, when Canada negotiated and signed the Halibut Treaty with the United States without seeking British approval, further demonstrating its newfound independence in foreign relations.

Canadian historian A.R.M. Lower described the significance of the Statute of Westminster, stating that the statute "came as close as was practical without revolutionary scissors to legislating the independence of the 'Dominions'." He suggested that December 11, 1931, the date the Statute of Westminster was passed, could be considered Canada's Independence Day, as it was the day Canada became a sovereign state. Although Canada did not yet have the power to amend its own constitution—the British North America Act (BNA Act) remained under the control of the British Parliament—the Statute of Westminster effectively made Canada the master of its own internal and foreign affairs.

The full autonomy over constitutional matters would come much later, with Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s patriation of the Constitution in 1982. However, by 1931, Canada was already taking significant steps toward full sovereignty. Another critical development occurred in 1949, when the Supreme Court of Canada replaced the British Privy Council as the highest court of appeal, marking the final legal break between Britain and Canada. Canada had thus evolved into a fully autonomous nation, with its own legal and political systems entirely under its own control.

The passage of the Statute of Westminster is perhaps one of the most important moments in Canadian history because it marked Canada’s formal emergence as an independent country. While Canada’s road to full sovereignty was a gradual process, the events of the 1926 Imperial Conference, the Balfour Report, and the Statute of Westminster in 1931 represent key milestones on that journey. By achieving legal and political independence through peaceful means and mutual consent, Canada’s evolution into a sovereign nation was a unique model of decolonization within the British Empire.

The Balfour Report and the Statute of Westminster also paved the way for Canada’s evolving identity on the world stage. By the time World War II erupted in 1939, Canada was able to make its own decision to enter the conflict, a decision it made one week after Britain declared war on Germany. This independence of action reflected the changes that had been put in place during the interwar years and demonstrated Canada’s ability to act autonomously in international affairs. The principles of the Statute of Westminster also laid the groundwork for Canada’s post-war role in the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, and as a founding member of NATO.

In conclusion, the events that took place between the 1926 Imperial Conference and the passage of the Statute of Westminster in 1931 were of profound importance to Canada’s development as a nation. They represented the culmination of decades of constitutional evolution and growing national consciousness. The recognition of Canadian autonomy over its internal and external affairs allowed the country to forge its own path, develop its own foreign policy, and grow into the fully independent state that it is today. These milestones reflect the unique nature of Canada's peaceful transition from a British colony to a sovereign nation, a process achieved through diplomacy, mutual respect, and cooperation.

Cite Article : www.canadahistory.com/sections/documents