CANADA HISTORY

St Lawrence Cruise

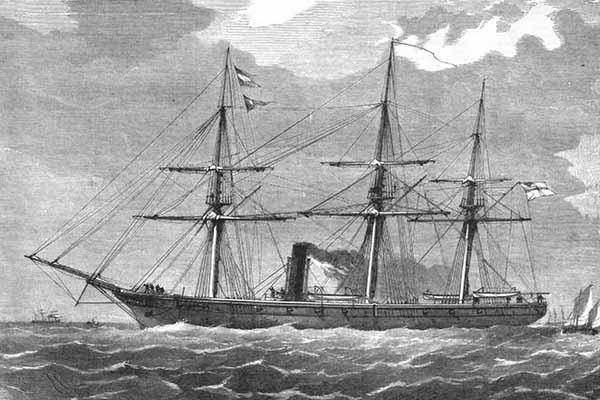

The journey undertaken by the representatives from the Province of Canada down the St. Lawrence River to Prince Edward Island in September 1864 was an important prelude to one of the most significant political events in Canadian history—the Charlottetown Conference. This trip was more than a leisurely cruise; it was a critical opportunity for the Canadian delegation to solidify their strategy and present a unified front in the push for Confederation. As they sailed towards Charlottetown, the delegates refined their arguments, engaged in discussions, and, perhaps most importantly, built a sense of camaraderie that would serve them well in the discussions ahead.

The Canadian delegation was composed of some of the most prominent political figures of the time, including John A. Macdonald, George-Étienne Cartier, Alexander Galt, George Brown, D'Arcy McGee, and others. These men represented a coalition of interests from both Canada West (now Ontario) and Canada East (now Quebec), regions that had long been mired in political gridlock due to their differing linguistic, religious, and cultural backgrounds. Despite their differences, these leaders shared a common goal—to create a federation that would unify the British North American colonies and provide a solution to the political and economic challenges that faced the provinces.

The political context at the time was critical. In the early 1860s, Canada West and Canada East were struggling with political paralysis due to the equal representation of the two regions in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada. As population growth in Canada West outpaced that of Canada East, leaders such as George Brown argued for "representation by population," a proposal fiercely opposed by the French-speaking population of Canada East. Meanwhile, the Maritime colonies—New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and possibly Newfoundland—had their own concerns about economic stagnation and the possibility of being overshadowed by larger, more populous provinces.

With these challenges in mind, the idea of a larger confederation was gaining traction. However, the Charlottetown Conference had originally been convened to discuss a Maritime Union between Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. It was only through the persistence and political savvy of the Canadian leaders that they managed to secure an invitation to present their vision for a broader union of all the colonies, including Canada and the Maritimes.

The cruise down the St. Lawrence served multiple purposes. In addition to being a practical means of transportation, it was a chance for the Canadian representatives to hammer out a unified strategy. As George Brown described in his letter to his wife, the atmosphere on board was one of camaraderie and optimism. The Canadian delegation took advantage of the time to refine their proposals, debate strategy, and ensure that they would present a cohesive message when they arrived in Charlottetown. They knew that they would need to persuade the Maritime delegates—many of whom were initially focused solely on Maritime Union—that a larger confederation would be in their best interest.

Brown’s letter paints a vivid picture of the journey, emphasizing the sense of occasion and the delegates’ confidence. He writes about the “fine weather,” the camaraderie among the group, and the spirit of goodwill that prevailed. This spirit extended to the hospitality with which they were received upon their arrival in Charlottetown, where they were greeted by bands and curious locals. The delegates’ arrival, complete with well-dressed oarsmen and an air of formality, underscored the importance of the event.

The Canadian delegation, well-prepared and united, was able to take center stage at the Charlottetown Conference, despite the fact that the meeting had originally been intended to discuss Maritime Union alone. The Canadians presented a compelling case for Confederation, outlining several key advantages:

Expanded markets: A larger union would create greater economic opportunities by opening up new markets between the provinces, stimulating trade and investment.

Intercolonial railway: The construction of a railway connecting the provinces would not only facilitate trade but also enhance communication and defense, especially in light of American expansionism.

Defense against American encroachment: A united British North America would be better positioned to defend itself against potential threats from the United States, particularly in the aftermath of the American Civil War.

Political influence: Maritime politicians would gain access to a larger stage, with increased opportunities for career advancement and participation in national governance.

Cultural protections: The federal system would allow individual provinces to retain control over local matters, ensuring that distinct cultural identities, such as the French Catholic population in Quebec or the unique concerns of Prince Edward Island, would be protected.

The Canadians’ presentation was well-received, and by the end of the conference, the Maritime Union had been set aside in favor of discussions on a larger confederation. The momentum generated at Charlottetown would carry forward to the Quebec Conference in October 1864, where the detailed terms of Confederation were debated and refined.

The Charlottetown Conference marked a turning point in the history of Canada. What had begun as a relatively small-scale meeting of Maritime leaders became the first step toward the creation of a new nation. The Canadians’ well-timed intervention, their unified approach, and their compelling vision for the future of British North America ultimately laid the foundation for the birth of Canada as a federal state in 1867.

In the broader context of Canadian history, the Charlottetown Conference demonstrated the importance of political leadership, negotiation, and compromise. The success of the Canadian delegation in convincing the Maritime representatives to pursue a larger union was not only a victory for the proponents of Confederation but also a reflection of the evolving political landscape of British North America. The conference set the stage for further discussions that would ultimately lead to the passage of the British North America Act in 1867, bringing together Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia as the founding provinces of the new Dominion of Canada.

The journey down the St. Lawrence, with its air of optimism and camaraderie, serves as a reminder that Confederation was not a foregone conclusion but the result of careful planning, persuasive argument, and, above all, a shared vision for the future of a united British North America. Without the political foresight of leaders like John A. Macdonald, George Brown, and Georges-Étienne Cartier, the path to Confederation might have taken a very different course. The cruise to Charlottetown thus became a critical chapter in the story of Canada’s birth.

Cite Article : www.canadahistory.com/sections/documents