CANADA HISTORY

Pan Federalism

The movement toward Confederation in British North America in the 1860s was driven by a complex interplay of political, economic, and strategic factors. Although calls for greater unity had been expressed in various parts of the British colonies, the general sentiment increasingly leaned toward the idea of a Federal Union. This growing inclination was rooted in the realization that a stronger, unified government could help address the collective challenges the colonies faced while still respecting their individual needs and identities. By looking to the examples of other nations, including the United States and its struggles, the political leadership in British North America began to shape a vision of a nation that would span from coast to coast.

At the heart of this movement was the desire for a union that could balance regional autonomy with centralized authority. The idea of federalism—where the central government held overarching powers, but individual provinces or colonies retained control over local matters—was becoming increasingly attractive. For the leaders of Canada West (modern Ontario) and Canada East (modern Quebec), political deadlock had crippled progress, as both regions struggled to reconcile their differences. In the Maritime provinces, including Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, there was also a recognition that a more extensive union could open new opportunities for economic growth, improved defense, and better infrastructure.

An essential factor shaping the Confederation debate was the example of the United States, which was undergoing the Civil War from 1861 to 1865. The U.S. struggle to reconcile states' rights with federal authority, and the resulting bloodshed, was a sobering lesson for British North American leaders. They saw the fragility of a system where local interests could so strongly challenge national unity. This experience underscored the need for a stable federal system that would prevent such division. The Canadian leaders, particularly John A. Macdonald, George-Étienne Cartier, and George Brown, took note of these lessons as they debated the structure of what would become the Dominion of Canada.

John A. Macdonald, who emerged as the primary architect of Confederation, had a larger vision that extended far beyond the existing colonies. He and others foresaw a British North America that stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from the United States border to the Arctic hinterland. This vision of a vast and united British colony would not only enhance the colonies' economic prospects but also serve as a powerful counterweight to the growing influence of the United States, whose doctrine of Manifest Destiny implied territorial expansion across the North American continent.

In addition to the political and strategic motivations, British interests also played a significant role in encouraging Confederation. By the mid-19th century, Britain was increasingly inclined to see its North American colonies achieve greater self-sufficiency. The cost of maintaining and defending the colonies was significant, and with the U.S. expanding westward and the Spanish and Russian empires present on the Pacific coast, Britain saw the value in creating a self-governing dominion that could take on more responsibility for its defense and governance. Britain ruled not only the Colonies of Canada, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland, Vancouver Island, and British Columbia, but it also held sway over the vast interior lands administered by the Hudson’s Bay Company.

These interior lands, which encompassed the vast expanse of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory, represented a critical part of the Confederation dream. Incorporating this territory into a new nation would make British North America larger than the United States and provide the new Dominion with the resources and geographic reach to become a significant player on the world stage. This vision also included the Prairies, which held untapped agricultural potential, and the Pacific coast, which offered access to lucrative trade routes with Asia. A confederated Canada, united by railways and steamships, could effectively tie together its disparate regions and create a transcontinental nation.

The development of railway technology was key to making this dream a reality. A railway linking the provinces of Ontario, Quebec, the Maritimes, and the western territories would not only serve as a tool for economic development but also as a defensive measure against potential American aggression. The expansion of the Intercolonial Railway was a crucial component of the Confederation plan, promising improved trade, faster transportation, and better communication between the distant regions of the new Dominion.

The political discussions leading up to Confederation also highlighted the need for regional accommodations to ensure the participation of all the colonies. Each region had its unique challenges and priorities. For instance, Prince Edward Island had longstanding issues with absentee landlords and demanded the buyout of these landlords as a condition for joining Confederation. Quebec, with its distinct French-speaking Catholic population, required guarantees that its culture, language, and legal system would be protected. The Maritime provinces wanted assurances that they would not be marginalized within a larger union dominated by the more populous Canada West and Canada East. These concerns were addressed through the creation of a Federal Union, where each province retained significant control over its local affairs.

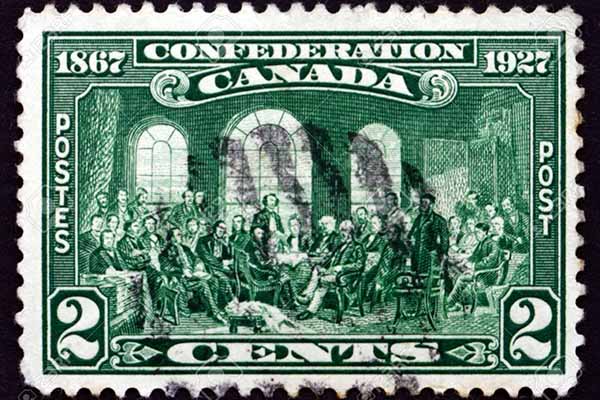

The conferences at Charlottetown (1864), Quebec (1864), and London (1866) were instrumental in working out the details of this complex political arrangement. At these meetings, leaders from the various colonies, including John A. Macdonald, Georges-Étienne Cartier, Charles Tupper, and others, hammered out the structure of the new government. They agreed on a bicameral parliamentary system modeled after the British system, with a House of Commons representing the population proportionally and a Senate providing equal regional representation. The constitution, known as the British North America Act, was finalized in 1867, laying the legal foundation for Confederation.

On July 1, 1867, Canada was born as a federal Dominion within the British Empire, uniting Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. Over time, other provinces and territories would join this union, including British Columbia in 1871 and Prince Edward Island in 1873. The vast Hudson’s Bay Company territories would be purchased by the new Canadian government, paving the way for the expansion of Manitoba and the eventual formation of Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905.

The move toward Confederation was a pivotal moment in Canadian history, representing not only the creation of a new political entity but also the realization of a vision for a vast and united nation. It addressed the immediate political challenges of the time—such as the deadlock in Canada’s government and the need for stronger defense—but it also set the stage for the economic development and national growth that would follow in the decades to come. Confederation was the culmination of a long process of negotiation, compromise, and visionary thinking, and it remains one of the most significant achievements in the formation of modern Canada.

Cite Article : www.canadahistory.com/sections/documents