CANADA HISTORY

Canada's Proposals

The political deadlock in the Union of the Canadas during the 1860s, characterized by stagnation and an inability to pass important reforms, had paralyzed progress in both Canada East (modern-day Quebec) and Canada West (modern-day Ontario). It seemed logical to assume that the British government might be hesitant to support similar political experiments elsewhere in its colonies, but in fact, the opposite was true. Britain saw the potential for a larger political union as a solution to many of the internal problems facing its North American colonies, particularly the ongoing deadlock within the Canadas.

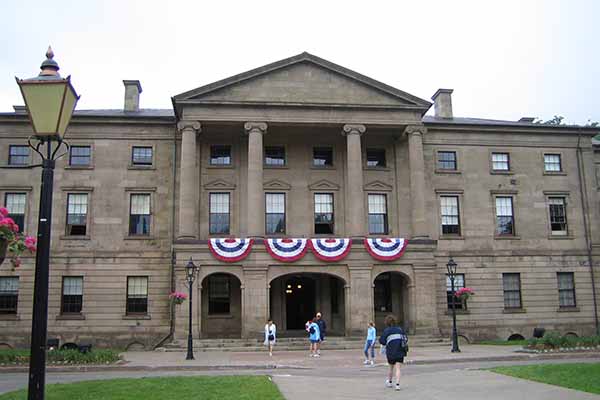

One of the earliest advocates of political union was Francis Bond Head, the Governor of New Brunswick. He led a push for a Maritime Union, which would bring together New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and possibly Newfoundland into a single political entity. This idea gained traction in 1863 and 1864, as Bond Head actively campaigned for union in the hope of stabilizing the region and fostering economic growth. The colonial legislatures of the Maritime provinces agreed to meet and discuss the proposal, gathering in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island on September 1, 1864, for what would become a crucial conference in Canadian history.

While this conference was initially intended to focus on Maritime Union, news of the meeting reached the Canadas, where leaders like John A. Macdonald saw a greater opportunity: the formation of a larger union that could solve the problems not only of the Maritimes but also of Canada East and Canada West. Macdonald, realizing the potential benefits of such a union, led a delegation that included members of both the government and the opposition from the Canadas. In the weeks leading up to the conference, many Canadian representatives spent time visiting the Maritime colonies, building relationships with local leaders and gauging support for the idea of a broader political union.

When the Canadian delegation arrived in Charlottetown, they found that the Maritime Union Conference had already begun. However, they quickly managed to shift the focus of the discussions. Macdonald and his colleagues presented a compelling case for a larger union of all the British North American colonies, outlining several key advantages that such a union would offer.

Firstly, they argued that the creation of an expanded union would open up new markets for each colony, fostering economic growth through increased trade and the free movement of goods between the provinces. This would benefit not only the Canadas but also the Maritimes, which were in need of economic diversification and a wider reach for their products.

Secondly, interregional investment could help build up industries and infrastructure across the colonies, further boosting economic development. The pooling of financial and natural resources from various colonies would create opportunities for new projects and commercial ventures that were previously unattainable in the smaller, isolated colonial economies.

One of the most critical points made by the Canadians was the need for an intercolonial railway. Such a railway, they argued, would not only improve communication and commerce between the regions but would also ensure greater military and strategic cohesion in the face of potential American encroachment. At the time, fears of expansionist U.S. policies, particularly after the American Civil War, were high, and a united British North America would be better positioned to defend itself from any threats of annexation or invasion.

The political advantages of a larger union were also emphasized. For the Maritime politicians, participation in a broader political landscape would offer new opportunities for career advancement and a more significant role on the national stage. Rather than being limited to provincial matters, these leaders could now influence the development of a new nation.

A union would also reduce the risks of smaller, regional governments working at cross purposes, which could lead to disunity and inefficiency. By centralizing certain aspects of governance, the colonies could present a united front on both domestic and international issues.

An important aspect of the proposal was the guarantee of regional rights and protections, which would safeguard the unique cultures and interests of each province. This was particularly important to Prince Edward Island, which sought the buyout of absentee landowners—many of whom lived in Britain—as a condition of its participation in the union. The delegates recognized that for such a union to work, each colony needed assurances that its individual concerns would be respected and addressed within the larger political framework.

From a political perspective, many of the arguments made by John A. Macdonald and his Canadian colleagues echoed those found in the Federalist Papers of the United States, written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay. These papers had laid the intellectual foundation for the American Constitution, promoting a strong central government that balanced power with individual state rights. The Canadian leaders drew from these ideas to promote a federal structure that could resolve the ongoing political deadlock and create a more effective system of governance for all the colonies.

By the time the Charlottetown Conference concluded, the idea of Maritime Union had been largely set aside in favor of the larger project: a British North American Union. The conference participants, inspired by the vision of a new political entity that would include not just the Maritimes but also the Canadas and possibly other colonies, agreed to meet again in Quebec City in October 1864 to continue working out the details.

The Charlottetown Conference of 1864, initially intended as a discussion about Maritime Union, became the foundation for Canadian Confederation. The idea of a unified political entity that could stand on its own, economically and politically, was compelling enough to shift the focus from regional concerns to a broader national vision. It marked the beginning of a process that would lead to the creation of Canada as a nation in 1867, with the British North America Act serving as the legislative framework for this new union.

This moment was significant in Canadian history because it demonstrated the colonies' growing desire for self-governance and greater autonomy from Britain. It also showcased the political skill and vision of leaders like John A. Macdonald, who recognized the need for unity and compromise to build a stronger, more stable nation. The eventual success of Confederation would lay the foundation for Canada's future development, setting it on a path toward independence and establishing the framework for modern Canadian federalism.

In conclusion, the Charlottetown Conference and the subsequent discussions were pivotal in shaping the political landscape of British North America. What began as a meeting focused on Maritime Union quickly evolved into the first steps toward Canadian Confederation, a process that would unite the diverse colonies of British North America into one political entity. The vision and leadership displayed by the Canadian delegation in Charlottetown set in motion the creation of a new nation, one that continues to play a central role in Canadian identity and history.

Cite Article : www.canadahistory.com/sections/documents