CANADA HISTORY - War

1760 Campaign

The fall of Quebec in 1759 was a monumental victory for the British in the Seven Years' War, but it did not spell the end of the French resistance in North America. The French field army, though battered and demoralized, had not been captured with the city. Montreal, the remaining stronghold of New France, still stood defiant, and it would take another campaign to complete the conquest of Canada. The British, under General James Murray, held Quebec through the brutal winter of 1759-60, consolidating their tenuous hold on the city, while the French forces regrouped under Montcalm’s successor, the capable Chevalier de Lévis. The political and military stakes were high, and both sides understood that the next campaign would determine the fate of the continent.

As the snow began to melt and spring arrived in 1760, Lévis, fully aware that this was his final chance to save New France, led his army from Montreal to recapture Quebec. His forces, while diminished, were well-trained and motivated, hoping to deliver a crushing blow to British forces before reinforcements could arrive from across the Atlantic. On April 28, 1760, at the Battle of Sainte-Foy, Murray, determined to meet the French in the open, marched out of Quebec to engage Lévis. The battle, fought in deep snow, was a brutal and bloody affair. The French troops, under Lévis's skillful command, fought with the desperation of men defending their homeland, and Murray’s forces, though valiant, were outmatched. In one of the last great victories of New France, Lévis decisively defeated Murray, driving him back within the walls of Quebec.

Murray’s defeat at Sainte-Foy put the British position in Quebec in jeopardy. Lévis moved swiftly to besiege the city, and for a brief moment, it seemed as though the tide of the war might turn in favor of the French. The colony could still have been saved if France had been able to send substantial reinforcements. A strong French fleet, carrying troops and supplies, might have lifted the siege and allowed New France to hold on, at least temporarily, to its key territories. But the French government, mired in its own struggles in Europe and hamstrung by British naval superiority, was unable to provide the support that Lévis so desperately needed. The North Atlantic, dominated by the powerful Royal Navy, effectively cut off New France from the mother country. When ships finally sailed up the St. Lawrence River in May, it was not the French fleet bringing salvation, but a British squadron. With the arrival of British reinforcements, Lévis’s hopes were dashed, and he was forced to lift the siege of Quebec.

The situation now turned decisively in favor of the British. Determined to bring an end to French resistance in Canada once and for all, William Pitt, Britain’s master strategist, once again called on the British colonies and military for a final, overwhelming effort. He gave General Amherst, the cautious and methodical British commander-in-chief, full authority to plan the conquest of Montreal. Amherst devised a three-pronged strategy, a classic maneuver aimed at converging British forces from different directions on Montreal, leaving the French no room to maneuver or retreat. This plan, if executed properly, would ensure the complete and final collapse of New France.

Amherst’s strategy was as ambitious as it was calculated. He entrusted Brigadier William Haviland with one prong of the assault, ordering him to advance from the Lake Champlain region, driving through French defenses and descending on Montreal from the south. At the same time, General Murray, having secured Quebec, would sail up the St. Lawrence from the east, tightening the noose around Montreal. The main British force, however, would be under Amherst’s own command. Leading an army of over 10,000 men, Amherst was to descend the St. Lawrence River from Lake Ontario, sweeping through the western French defenses and converging on Montreal. This coordinated, multi-directional attack was designed to prevent the French from concentrating their forces or retreating westward, where outposts like Fort Detroit were still nominally under French control. Amherst’s plan left the French with little room for error—there would be no escape.

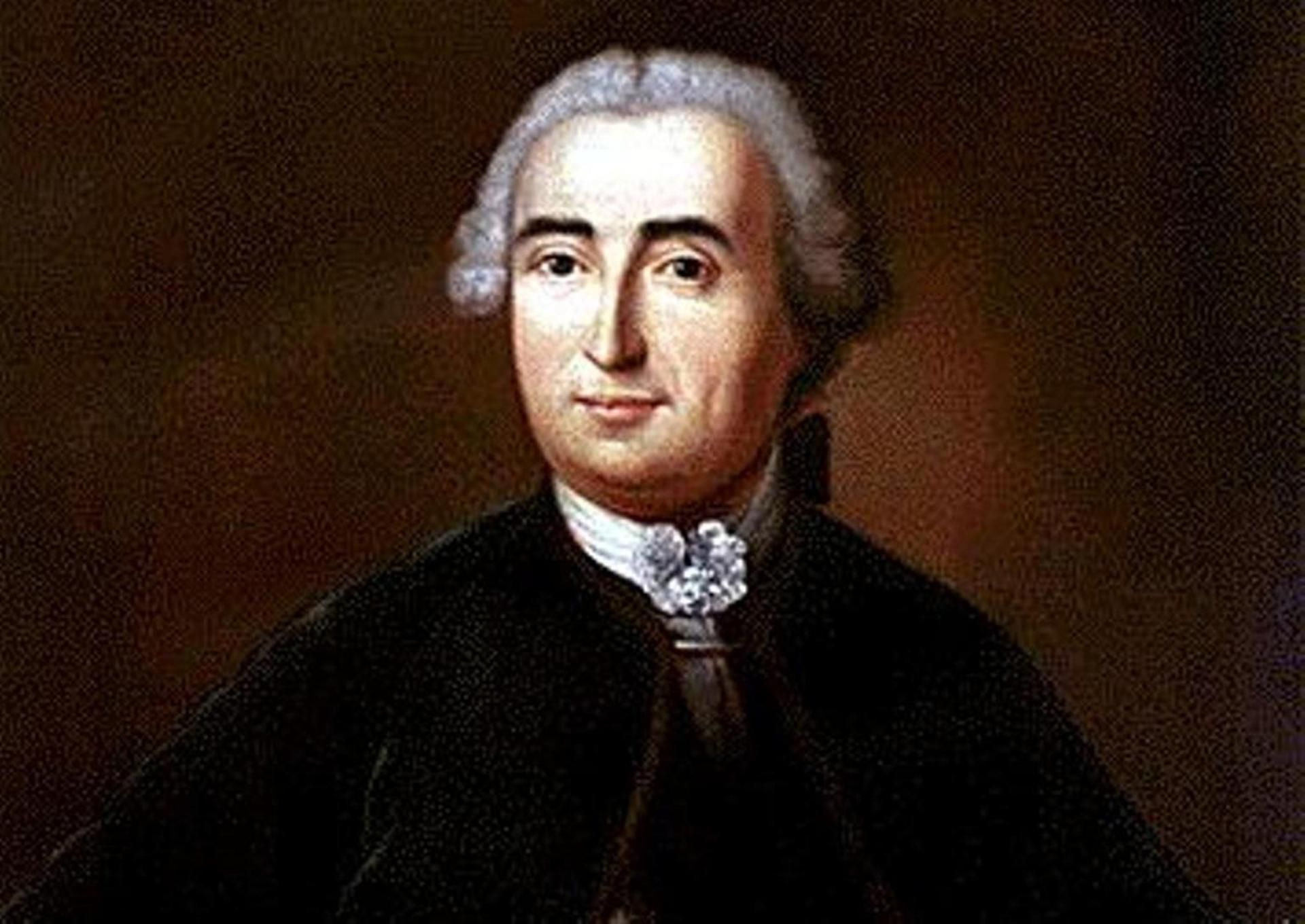

The French, desperately clinging to their last stronghold, hoped to counter this strategy by striking at each British column in turn. The French forces, led by Lévis and Governor Vaudreuil, were aware that they lacked the strength to confront the British in a direct engagement. Their best hope was to defeat the smaller British detachments individually, perhaps even forcing one or more of the British armies to retreat. However, this plan required speed, coordination, and luck, none of which the French commanders possessed in sufficient measure by this stage of the war. Their forces were thinly stretched, demoralized, and facing an enemy whose numerical superiority had become overwhelming.

On the Lake Champlain front, Haviland’s advance proved irresistible. French forces, which had initially hoped to make a stand at Île aux Noix and St. Jean, were forced to abandon these positions as Haviland’s superior numbers and firepower made resistance futile. The French retreated in disarray, and Haviland's troops soon reached the St. Lawrence River, poised to join the other British forces in the assault on Montreal. Meanwhile, General Murray, with the benefit of British naval power, bypassed French garrisons along the St. Lawrence. The French outposts that he encountered posed no significant threat, and he swiftly sailed upriver, uniting his forces with Haviland's.

Amherst, however, faced a minor obstacle in his descent of the St. Lawrence. Fort de Lévis, a small French fortification situated on an island near the head of the St. Lawrence rapids, stood in his way. Though insignificant in the broader strategic picture, Amherst approached the fort with his characteristic thoroughness. He landed his artillery and systematically bombarded the fort until it was reduced to ruins. Though this victory was relatively small, it demonstrated Amherst’s disciplined approach, which left nothing to chance. Having dispatched the fort, Amherst continued his descent down the St. Lawrence, but not without difficulty. The treacherous rapids claimed many lives, prompting Amherst to remark in frustration, “I have suffered by the Rapides not by the enemy.” Still, he pressed on, eventually landing his forces on the island of Montreal.

In a remarkably well-coordinated maneuver, all three British columns converged on Montreal almost simultaneously, in what military historian Sir Julian Corbett described as “like the striking of a clock.” The sheer size of the British forces—some 17,000 men—was overwhelming. In contrast, the French defenders were a spent force. With desertions mounting and morale crumbling, Lévis and Vaudreuil had scarcely 2,000 men left to face the British juggernaut. They had no realistic prospect of holding out against such an overwhelming force. With no options left and their troops abandoning them in droves, Lévis and Vaudreuil were forced to surrender.

On September 8-9, 1760, Montreal capitulated to the British, and with it, the entirety of New France passed into British hands. The long struggle between France and Britain for dominance in North America had come to an end. It had been a war of staggering complexity, fought across multiple continents and involving the fates of empires. For Canada, the surrender of Montreal marked the close of a chapter that had begun with French exploration and settlement more than two centuries earlier. The French empire in North America was no more, its territories now part of the burgeoning British empire. The conquest of Canada was complete, and the stage was set for a new era in the history of the continent.

Cite Article : Reference: www.canadahistory.com/sections/documents/documents.html

Source: NA