CANADA HISTORY

Responsible

The move toward responsible government in Canada was a significant and gradual process that took place between 1839 and 1849, marking the end of oligarchic rule and the beginning of political accountability to elected representatives. This transformation occurred under the leadership of Charles Poulett Thomson, also known as Baron Sydenham, who was appointed Governor General of the Canadas in 1839. Sydenham’s role was pivotal in implementing the recommendations of Lord Durham's famous report, which had called for the unification of Upper and Lower Canada and the establishment of responsible government as a solution to the political unrest and rebellion that had rocked the colonies in the late 1830s.

One of Sydenham’s primary objectives upon his arrival was to unite Upper and Lower Canada into a single political entity. At the time, Upper Canada (modern-day Ontario) had a population of around 400,000, while Lower Canada (modern-day Quebec) had approximately 600,000 residents, of which 150,000 were of English descent. However, Upper Canada was saddled with over £1,000,000 in debt, while Lower Canada was relatively debt-free. The Union was designed, in part, to create a more stable financial situation by pooling resources, but it was also intended to address the political divisions that had led to rebellion, especially in Lower Canada, where French Canadians had long felt marginalized by the colonial administration.

Sydenham believed that uniting the two colonies would also address the issue of French-Canadian political power. The British government, reflecting Lord Durham’s views, hoped that by merging Upper and Lower Canada, the larger English-speaking population would eventually outnumber and overpower the French Canadians, leading to their assimilation into British culture and political life. The Union Act of 1840 created a single legislature with an equal number of representatives from both Upper and Lower Canada, even though Lower Canada had a larger population. The intention was clear: the English-speaking population, particularly those in Upper Canada, would gradually dominate the legislative assembly, passing laws that would erode French customs, language, and institutions.

However, Sydenham’s plan to use the Union to marginalize French Canadians was built on a flawed assumption—that English-speaking Canadians would form a unified voting bloc. In reality, political divisions among the English were just as pronounced as those between the French and English. Reformers in Upper Canada, disillusioned by the oligarchic rule of the "Family Compact" (the elite governing class in Upper Canada), found common cause with reform-minded politicians in Lower Canada, including French Canadians. This unexpected alliance between Upper Canadian reformers and Lower Canadian "bleu" (moderate French-Canadian politicians) thwarted Sydenham’s goal of creating an English-dominated legislature. Instead of uniting against French Canadians, the reformers from both sides worked together to advance democratic reforms and to protect the rights of French Canadians, challenging the notion that the French population could be easily overwhelmed by the English.

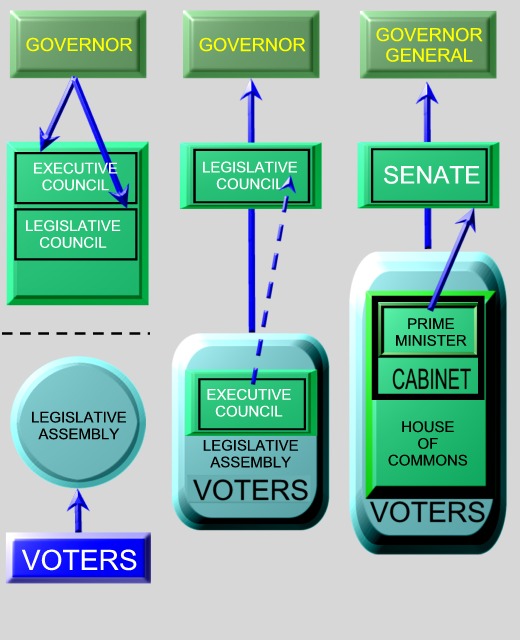

The next critical step in the move toward responsible government was shifting real power from the Governor General to the elected representatives of the Legislative Assembly. In the pre-responsible government era, governors held significant power, often acting in accordance with the interests of the British government and an unelected executive council composed of elite members of society, such as the Family Compact in Upper Canada. These oligarchic elites had little accountability to the people, leading to widespread frustration and unrest.

Sydenham's approach to reform was cautious but calculated. He recognized that in order to quell further rebellions and stabilize the political situation, power needed to be gradually transferred to elected representatives. This required that the Governor General select members of the Executive Council (the precursor to the Cabinet) from the elected Legislative Assembly, thereby creating a system in which the government would be accountable to the people. The real test of responsible government came in ensuring that these elected representatives had the authority to enact legislation and govern, rather than merely serving as advisors to the governor. Sydenham laid the foundation for this change, but the full realization of responsible government would take several more years.

The evolution of responsible government in Canada was not achieved through a single legislative change but rather through a series of actions and precedents that shifted political power gradually. One key element of this evolution was the increasing influence of the Legislative Assembly, which began to assert its authority over the executive branch. As reformers gained more seats in the Assembly, they pushed for greater control over decision-making, advocating for a system in which the government would only remain in power if it had the confidence of the elected representatives.

By 1848, the principle of responsible government had become firmly entrenched. Governors were expected to appoint executive councilors who could command the support of the majority in the Legislative Assembly. This change was crucial in shifting the balance of power away from the governor and the British-appointed elites toward the elected representatives of the people. The eventual acceptance of responsible government represented a significant victory for the reform movement, particularly for figures like Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine, who championed democratic reforms and the protection of French-Canadian rights.

The transition to responsible government was not without its challenges. Governors like Sydenham and his successors had to navigate the political complexities of uniting two very different colonies, managing tensions between French and English populations, and gradually relinquishing their power in favor of elected representatives. The process also required cooperation and compromise between reformers from both Upper and Lower Canada, who had to overcome deep-seated political and cultural differences in order to achieve their shared goals.

The establishment of responsible government in the Canadas was a pivotal moment in Canadian history, laying the groundwork for the eventual creation of a united Canadian Confederation in 1867. It marked the beginning of a political system based on democratic principles, where the government would be accountable to the people through their elected representatives. The lessons learned during this period of political evolution would shape the development of Canadian democracy for generations to come.

The importance of this transition cannot be overstated. It not only represented a shift in the balance of power within Canada but also demonstrated the ability of the colonies to adopt and adapt British parliamentary principles to their own unique context. The move toward responsible government ensured that Canada would develop as a self-governing entity, capable of managing its own affairs and protecting the rights and interests of its diverse population, including the French Canadians who had been at the center of political unrest. In this way, the transition to responsible government set the stage for the peaceful and democratic formation of Canada as a nation, solidifying its place within the British Empire while laying the foundation for its eventual independence.

Cite Article : www.canadahistory.com/sections/documents