CANADA HISTORY - Culture-Group of 7

Lauren Harris

Lawren Stewart Harris, born on October 23, 1885, in Brantford, Ontario, was destined to become one of the most celebrated and influential artists in Canadian history. His early life was shaped by privilege and comfort. The Harris family was a pillar of Canadian society—his father was a prosperous industrialist who co-founded the Massey-Harris Company, which manufactured agricultural equipment. Lawren grew up in an environment that valued culture, education, and philanthropy. He was afforded every advantage, including access to the best schools and the freedom to travel. But beneath the ease and refinement of his early years, there stirred in young Lawren a restlessness, a desire to break beyond the conventions of his upbringing and explore the deeper meanings of life and art.

Harris’s early education was shaped by private tutoring and attendance at elite institutions, but it was art that captured his imagination. He showed an early talent for drawing, and this passion led him to the University of Toronto, where he briefly studied before leaving to pursue a more focused artistic path. Like many young artists of his generation, Harris sought to refine his skills abroad. In 1904, he traveled to Berlin, where he enrolled at the prestigious Berlin Royal Academy of Fine Arts. His time in Germany exposed him to the burgeoning movements of modernism and Expressionism, which challenged the academic traditions in which he had been trained. These European influences would later meld with Harris’s own vision, but for the moment, they set him on a course of self-discovery.

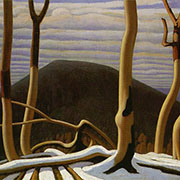

Harris returned to Canada in 1908, at a time when Canadian art was largely conservative and beholden to European styles. He quickly established himself within the Toronto art scene, but it was the discovery of the rugged Canadian landscape that ignited his creative fire. It was in the wilderness of Northern Ontario that Harris found the subject matter that would become central to his artistic life: the vast, untouched expanses of land and sky, the dramatic interplay of light and shadow on snow-covered mountains, and the sublime, almost spiritual beauty of Canada’s north. His artistic journey, however, was not a solitary one. Harris was a natural leader and a man of intellectual curiosity, and he sought out other artists who shared his desire to create something uniquely Canadian.

In 1911, Harris met J.E.H. MacDonald, a painter and fellow seeker of a Canadian artistic identity. This meeting marked the beginning of what would become one of the most important collaborations in Canadian art history. Through MacDonald, Harris was introduced to a circle of artists, including Arthur Lismer, Frederick Varley, A.Y. Jackson, and Franklin Carmichael. These men, along with Tom Thomson, shared a belief that the Canadian landscape offered a wealth of inspiration, but they also believed that the art of Canada needed to break free from the shackles of European influence. Harris and his fellow artists spent long periods exploring the wilderness, sketching and painting the rugged beauty of places like Algonquin Park, Georgian Bay, and the north shore of Lake Superior.

Harris’s leadership in this group, which would later become known as the Group of Seven, was critical. He was the driving force behind their vision, both intellectually and financially. His wealth allowed him to fund trips into the wilderness and to support the efforts of his fellow artists, many of whom struggled financially. In 1920, the Group of Seven held their first exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario), and while the critical reception was mixed, it marked the beginning of a movement that would revolutionize Canadian art.

For Harris, painting was not just a visual exercise but a spiritual one. He believed deeply in the power of art to express something transcendent, something that lay beyond the physical world. His early works, such as North Shore, Lake Superior (1926), reflect this philosophy. In this painting, the stark landscape is rendered with a simplicity that emphasizes the vastness and solitude of the land. The forms are stripped of unnecessary detail, creating a sense of purity and clarity. Harris’s use of color—cold blues, whites, and grays—evokes the chill and isolation of the northern wilderness, but there is also a quiet, meditative quality to the painting, as if the landscape itself holds the key to some deeper truth.

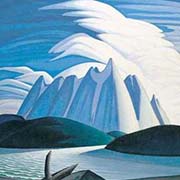

Throughout the 1920s, Harris continued to explore the landscapes of Canada, particularly the Rocky Mountains and the Arctic. These trips resulted in some of his most iconic works, including Mount Lefroy (1930) and Lake and Mountains (1928). In these paintings, Harris’s style became increasingly abstract. He sought to move beyond mere representation and instead convey the spiritual essence of the land. His mountains are not simply geological formations; they are symbols of permanence, strength, and the divine. Harris’s later works, with their simplified forms and bold, almost mystical use of color, reveal the influence of his growing interest in Theosophy, a spiritual movement that sought to explore the connections between art, science, and religion. Theosophy’s emphasis on the search for higher truth through contemplation and the exploration of the unseen world resonated deeply with Harris, and it profoundly shaped his artistic philosophy.

Harris’s contributions to Canadian art went beyond his own painting. He was a tireless advocate for the importance of art in Canadian culture, and he played a key role in establishing the Canadian Group of Painters in 1933, following the disbandment of the Group of Seven. He was also an influential teacher and mentor, helping to guide the careers of younger artists who shared his vision for a national art movement. Harris’s dedication to the idea of a distinctly Canadian art never wavered, and his efforts helped to establish the cultural foundations upon which much of Canadian art would be built.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Harris’s work became increasingly abstract, as he sought to strip away the physical details of the landscape and focus on its spiritual core. His later works, such as Composition (1933), are marked by a reduction of form and an emphasis on geometric shapes and color. These paintings, while more abstract than his earlier work, are still deeply connected to the Canadian landscape. The mountains, lakes, and skies of his earlier paintings have been distilled into their most essential forms, but they retain the sense of awe and reverence that characterized all of Harris’s work.

By the time of his death in 1970, Lawren Harris had become a towering figure in Canadian art. His legacy, both as an artist and as a leader of the Group of Seven, is profound. His paintings, with their bold colors, dramatic forms, and spiritual depth, helped to define Canada’s visual identity. Through his work, Harris showed Canadians that their landscape—vast, wild, and untamed—was not just a backdrop for their lives but a source of meaning and inspiration. His vision of the Canadian wilderness as a place of spiritual power and transcendence continues to resonate today, not only in the art world but in the broader cultural consciousness of the nation.

Harris’s contribution to Canada extends beyond his artistic achievements. He helped to create a sense of national pride in the country’s natural beauty, and his work encouraged Canadians to see their landscape as something unique and worth celebrating. His paintings are more than just representations of mountains, lakes, and forests; they are expressions of a deep connection to the land, a connection that is central to the Canadian identity. Today, Harris’s works hang in galleries across the country, including the National Gallery of Canada, where they continue to inspire and awe new generations of viewers.

In the end, Lawren Harris was more than just an artist. He was a visionary who sought to capture not only the physical beauty of the land but its spiritual essence. His work helped to establish a uniquely Canadian style of art, one that celebrated the majesty of the wilderness while also exploring the deeper meanings behind it. Through his paintings, Harris expressed a reverence for the land that continues to resonate with Canadians today, reminding us of the power and beauty of the world that surrounds us. His legacy, like the mountains he so often painted, stands tall and enduring, a testament to the transformative power of art.